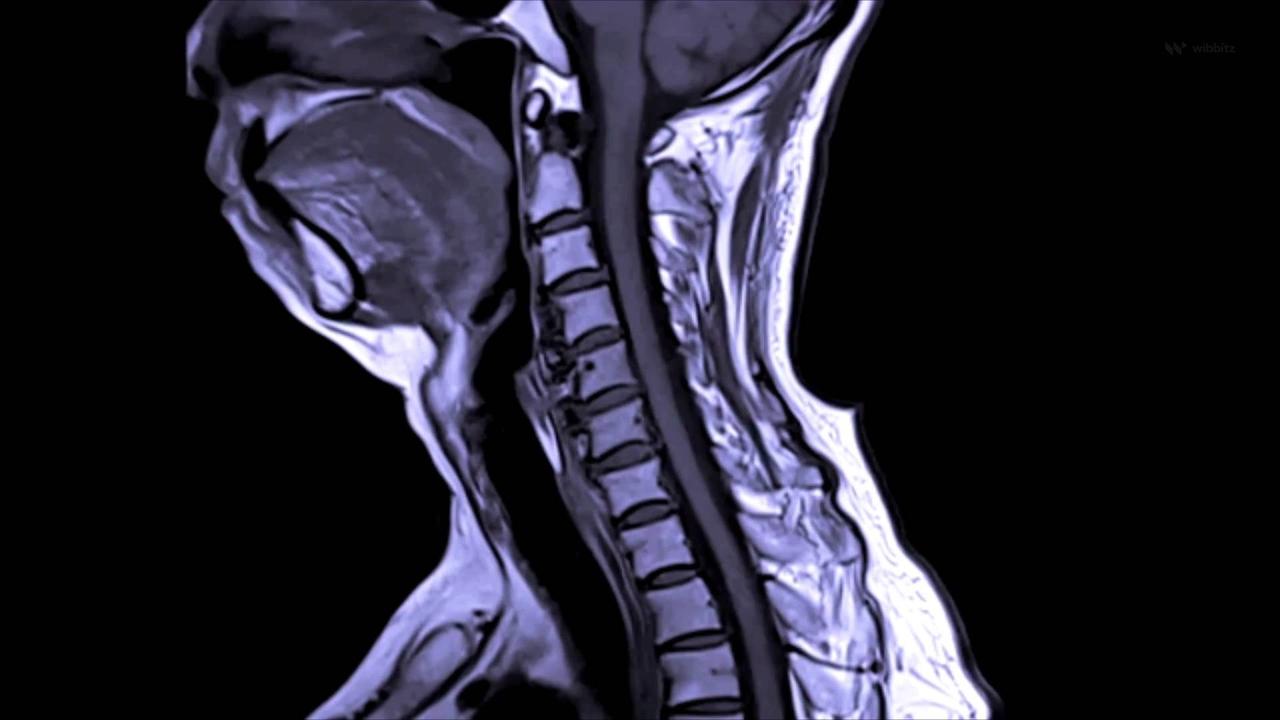

Neuroscience Breakthrough , Could Lead to New Treatments for , Spinal Cord Injuries.

'Newsweek' reports that neuroscientists have discovered that the human spinal cord is capable of making its own memories independent of the brain.

The discovery, which challenges previous ideas about neural circuits outside of the brain, could represent a breakthrough for people recovering from spinal cord injuries.

.

Learning and memory is often attributed as functions of the brain exclusively, Aya Takeoka, principal investigator at Japan's RIKEN Center for Brain Science, via 'Newsweek'.

Although scientists knew for more than a century that the spinal cord could learn and adapt movements in the absence of brain input, we did not know how the spinal cord learns and memorize what is has learned, Aya Takeoka, principal investigator at Japan's RIKEN Center for Brain Science, via 'Newsweek'.

Gaining insights into the underlying mechanism is essential if we want to understand the foundations of movement automaticity in healthy people and use this knowledge to improve recovery after spinal cord injury, Aya Takeoka, principal investigator at Japan's RIKEN Center for Brain Science, via 'Newsweek'.

The team of neuroscientists looked to demonstrate how spinal cord cells can adapt to sensory inputs without receiving any signals from the brain.

The two groups of nerve cells have distinct functions; learning cells are not needed for recalling what the spinal cord had learned, and memory cells were not needed for learning, Aya Takeoka, principal investigator at Japan's RIKEN Center for Brain Science, via 'Newsweek'.

The team hopes their results could help develop new rehabilitative training methods for patients with spinal cord damage.

Not only do these results challenge the prevailing notion that motor learning and memory are solely confined to brain circuits, but we showed that we could manipulate spinal cord motor recall, which has implications for therapies designed to improve recovery after spinal cord damage, Aya Takeoka, principal investigator at Japan's RIKEN Center for Brain Science, via 'Newsweek'.

The team's findings were published in the journal 'Science.'