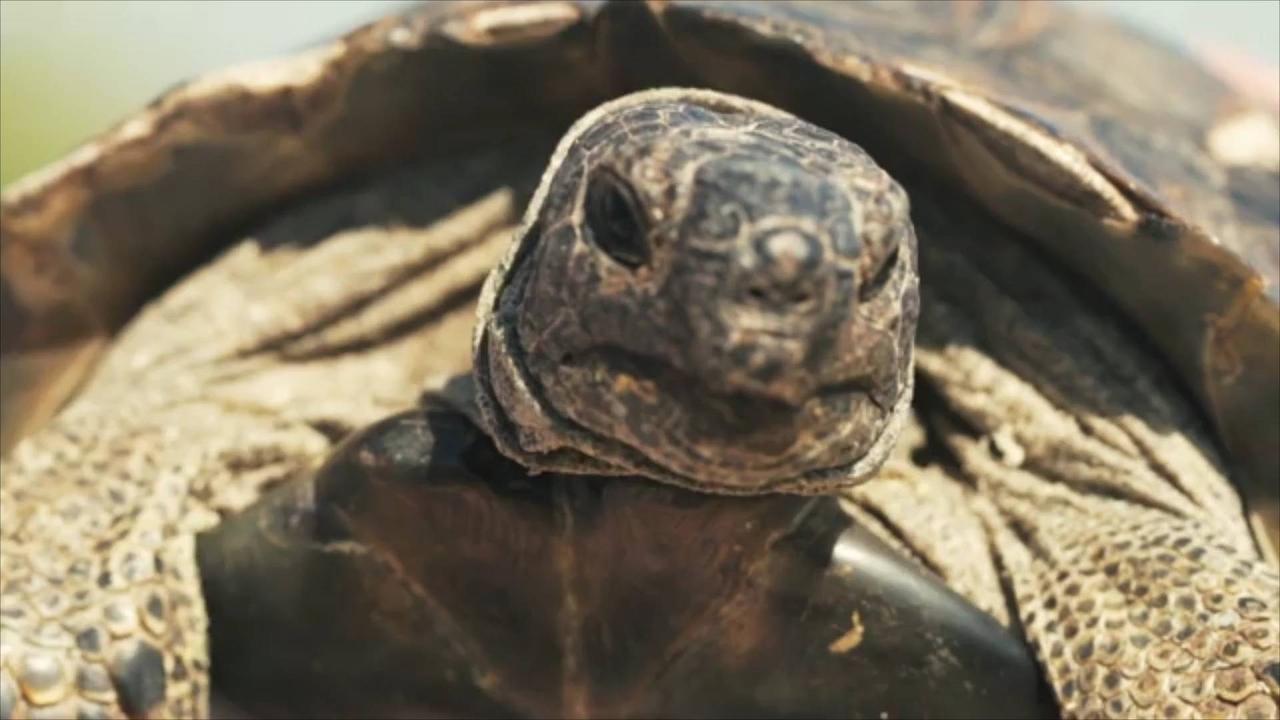

Researcher Makes First Ever, Recordings of Animals , Assumed to Be Mute.

NPR reports that a recent study found that many animal species long believed to be mute do, in fact, vocalize.

The paper's lead author, Gabriel Jorgewich Cohen, says that his project began after he read about a turtle in the Amazon making sounds.

.

The evolutionary biologist, who was working on his PhD at The University of Zurich, went on to record fifty species of turtles, as well as caecilians, tuataras and lungfish.

The evolutionary biologist, who was working on his PhD at The University of Zurich, went on to record fifty species of turtles, as well as caecilians, tuataras and lungfish.

The evolutionary biologist, who was working on his PhD at The University of Zurich, went on to record fifty species of turtles, as well as caecilians, tuataras and lungfish.

Actually every single animal I recorded made sounds, John Wiens, Professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, via NPR.

According to Cohen, the research points to a common ancestor that lived some 407 million years ago.

Neil Kelley, a paleontologist at Vanderbilt University, points out the difficulty of studying and tracking animal sounds over millions of years.

.

It's very hard to trace that in the fossil record, because sounds obviously don't fossilize and most vocal equipment is soft tissue-based, John Wiens, Professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, via NPR.

John Wiens, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, suggests that Cohen's work is an important step toward furthering our understanding.

If you don't record these sounds and report them, then there's no reason why anybody would study acoustic communication in those things.

You don't even know that they're making sounds, John Wiens, Professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, via NPR.

According to Wiens, the next step it to determine how these animals use these sounds to communicate with one another.